Nestled in a quiet, leafy Nairobi neighborhood just a stone’s throw from the throbbing of sounds of a sprawling city market, is a refuge where intersex, transgender and gender-nonconforming Kenyans can escape searing public judgment and discrimination.

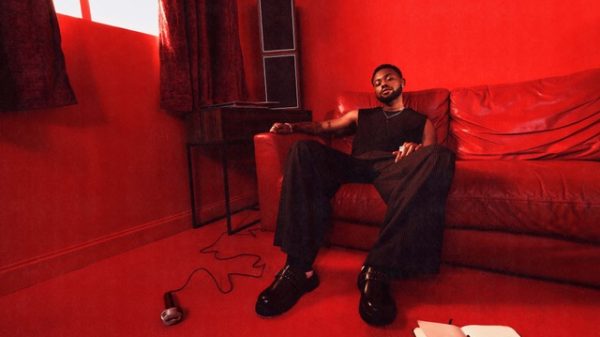

Inside, posters encouraging acceptance and love cover the foyers’ white walls; bathrooms boast gender-neutral signs. Downstairs, people share a late lunch of beans and rice while chatting on deep, soft couches. Upstairs, a transgender woman applies red lipstick without a mirror, then poses for a portrait, the sequins of her ruby red stilettos flicker in the long, afternoon light.

This safehouse is the heart of Jinsiangu, an organization advocating for the wellbeing of gender nonbinary people in Kenya. Its name comes from a combination of Swahili words meaning “my gender.”

Last month, Kenya completed the colossal effort to conduct its decennial census — from urban high rises to rural, tin-topped huts — and for the first time, it included a new gender category: intersex. This marked a first not only in Kenya but across the continent. Activists hope this will set a precedent for intersex rights in Kenya and around the globe, but intersex inclusion is still far from reality.

Globally, approximately 1-3% of the population are considered intersex and by those estimates, there could be as many as 1.4 million intersex people in Kenya, according to the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights.

At the helm of Jinsiangu is Kwaboka Kibagendi, an approachable man with an impassioned voice, who has pushed for intersex inclusion since he started the safe house six years ago.

Raised as a girl, Kibagendi, 33, didn’t realize he was intersex until six years ago. He blames cultural stigma, discrimination and a general lack of information as the reason he, and so many others, discover their identities late in life.

“When an intersex child is born, people wonder if it’s a curse,” he said. “Parents might separate, the child might be killed, or they might disown this child. So, if that’s the case, I ask, ‘Can our government make sure that there’s enough information about intersex people in society so that once these children are born so there’s no more harassment?’”

Kibagendi is one of the millions who identify as intersex — a term used when a person’s reproductive organs don’t fit within typical male or female characteristics. He sees the census as an opportunity to change public perception about the existence of a third gender, adding that an official tally is the first step in strengthening the rights of intersex people in the country.

“People try to deny this notion that African nations cannot spearhead anything that’s human rights-oriented. But I can tell you now, it’s like the world is realizing that we in Africa — and Kenya — are becoming more progressive in human rights. I am very proud,” he said.

He’s not alone.

“As an individual and intersex person, it was one of the happiest days of my life,” said James Karanja, director of Intersex Persons Society of Kenya.

Intersex people are deeply misunderstood in many parts of East Africa, where deviations of gender evoke beliefs about curses or mystical forces. Others see intersex as akin to homosexuality, a highly taboo topic that has polarized Kenyan courts in recent years.

“It’s because of this idea that if you’re intersex, then you’re an outcast,” Karanja said. “I’ve tried committing suicide — everyone in our organization has tried. You feel as though you don’t fit into society.”

“Kenyan laws only recognize the traditional binary markers of male and female, making it very difficult for intersex people to get recognition from the day they are born,” said Veronica Mwangi, deputy director of the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights. “This has a ripple effect for the official registration systems that come along.”

Accessing state-funded insurance programs, applying for travel documents and obtaining accurate birth certificates, which offer access to government services and employment, become enormous obstacles for intersex persons, Mwangi added.

Both Mwangi and Karanja sat on a task force that has advised Kenya’s Bureau of Statistics since February about the inclusion of a third gender. Karanja said the addition is one of a series of recommendations that he hopes will improve the lives of intersex Kenyans. Other recommendations include adding an intersex option to birth certificates, providing funding to cover the costs of gender realignment treatments, and ensuring corrective surgeries are completed in adulthood rather than at birth.

Others, however, questioned the government’s interest in counting intersex people as well as how the information would be used and by who.

“You have to come out of your home when the census person comes and I wondered, why record this? Just because I’m intersex? When you disclose something, you don’t know how people will react to it,” Sydney said. Sydney asked not to use his last name out of concerns for his personal safety.

Born Beatrice, Sydney, who identifies as a man, said he would prefer that the census uses a broader and more inclusive marker like “other” rather than “intersex,” or allow intersex people to change the gender on their birth certificates altogether.

“What the government needs to do, is not [give] us a third gender but put in policies that protect intersex people,” he said. “An intersex person is just a normal person, despite the challenges we’ve faced. The challenges are many, but we are just normal people. We were created by God, the same way other people were created by God.”And while Sydney was open to the census, in the end, the official never even asked Sydney about his gender.

“I was waiting for the third-gender question but he didn’t even mention it. I wondered, ‘Were they trained to do this work on intersex issues?’” he said. “I decided to keep quiet. If you don’t ask me, I won’t tell you.”

While the census provided a rare moment of recognition for intersex Kenyans, activists agreed it’s up to the community to continue to push for policies that protect and enhance the lives of intersex people in Kenya.

“The [census] conversation, it’s a gateway to a class of people who have historically been excluded from basic human rights,” said Karanja. “In the future, for people like me, I see ourselves being the pillar of society, people who are given a chance to contribute to society just like any other group.”

Sydney’s mind is also on the future of intersex people. “It’s high time we speak about these things. … I’ve gone through a lot and I would not like an intersex child that is born today to go through what I went through,” he said. “That’s why I choose to go out there and share this information.”