The year was 2009, and the DJ had just gone through a spectacular run of some of the biggest Nigerian songs of the era: 9ice’s “Gongo Aso,” “Lori Le” by X-Poject and P-Square’s “Do Me,” to name a few. I was at a family friend’s engagement party, and I had to sit down afterwards because my feet were starting to hurt after giving it my all on the dance floor while in heels.

It was a moment. Before then, the only music I had heard and fully accepted as “Nigerian” were the classic “oldies” from King Sunny Adé, Ebenezer Obey, Sonny Okosun or Fela—the staples my mom would play in the car on the way to school and all the other juju, fuji and highlife tracks that seemed to be mainstays at the “African hall parties” we’d frequent. These songs were familiar but they always felt like the music of a different time, of an older generation—especially to a first-generation Nigerian-American teenager like myself. If my friends and I wanted to hear something we felt we could dance to at these parties, we had to wait for the cursory run of “This Is How We Do It,” and the “Cha Cha Slide”—if that ever even came.

Around a decade ago, though, this began to change, and in between the typical party anthems, there’d be this newer sound (not yet commonly referred to as Afrobeats) that marked the “young people’s” time to hit the dance floor. It was a fairly new experience for most of us, hitting the “yahooze” and being able to enjoy music that felt like it was both wholly Nigerian and wholly for us at the same time. The parents didn’t seem to mind it either.

“Afrobeats,” as it’s now commonly referred to (though more precisely, we mean popular contemporary music, largely from Nigeria and Ghana) has been on the rise since, and several stars have emerged in the process—beginning with 2Baba, D’banj and star producer Don Jazzy in the early stages and expanding to include others like Wizkid, Tiwa Savage, Davido, Yemi Alade, the recently Grammy-nominated Burna Boy, and several others in between. It hasn’t only come from Nigerians either—artists across West Africa the likes of Ghana’s Sarkodie, Shatta Wale, Efya and more, and the British-Ivorian Afro B, with his hit song “Drogba (Joanna)” have also been central to bringing the sound of the continent to the mainstream. The sound has gone much further than local get togethers—it’s global, reaching new listeners and even helping bridge other sounds and subcultures like “afrofusion” and the alté scene. Although we may not have yet reached a consensus on whether or not it has fully “crossed over,” the growth and the influence of the sound—of the movement—has been undeniable, and thrilling to watch by any measure.

At OkayAfrica, we’ve been covering each shift and highlighting them in real-time. As we round out a decade, we wanted to stop and reflect on the last 10 years of the movement and gain some perspective on where it’s heading, so we asked 11 influential artists, critics and industry insiders to share stories about when they knew Afrobeats was going to become the cultural force that it is today (because while looking at charts and records are fun, there are personal memories that speak to its impact just as meaningfully). Some also shared their thoughts on its future and shed light on important discussions around maintaining cultural ownership as Afrobeats continues its ascent. Read on for their responses.

Lady Donli, Artist

“I think I became the most aware of the globalisation of afrobeats and afropop from two instances: the first was when I heard 2Face’s (now known as 2Baba) “African Queen” in the movie Fat Girls. I was still in secondary school then, but I remember being really fascinated. It kind of made me feel as though my dreams were actually valid on a global scale.

The second was when D’banj dropped the remix of “Mr. Endowed” featuring Snoop Dogg. I waited up and refreshed sites just to watch that video. It really just created a sense of awareness for me, it made me believe that afrobeats and Nigerian pop music could actually stretch out beyond borders. Now with the streaming era it’s becoming even more visible, the possibilities are endless. However, I still think there’s a whole lot of work to be done, but right now, [I think] this is a good starting point.

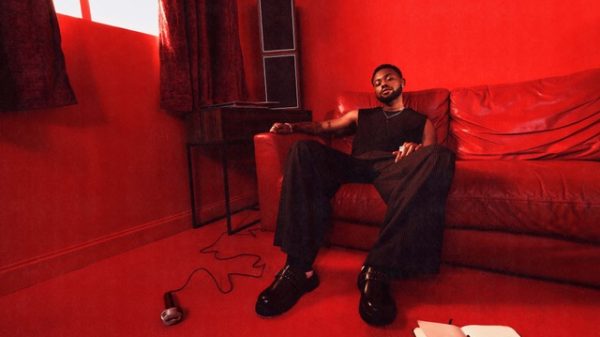

Davido, Artist

There wasn’t just one moment when I knew Naija music was going to blow, there have been different moments. It was just a good feeling coming from everywhere: social media, clubs, radio—it all happened at once. I can’t think of just one time, I thought “ok, yes we’re here.” It just gradually happened.

In terms of artists who set the foundation, you can’t forget Fela, you can’t forget D’banj and P-Square and 2Face (2Baba). The list goes on. These are people that were fighting for Nigerian music to get played on radio, and right now it’s happening. We can’t forget them.

We have done a lot for this movement. The movement is getting so big now, I see hundreds of people behind me coming up. I feel like it’s in good hands, I’m just happy that being African right now is a good thing. A couple years back, it wasn’t cool.

Efya, Artist

The first One Africa concert at the Barclay’s Center in New York [in 2016]. I don’t think it’s something that we thought was going to be possible 10 years ago. I think at a certain point, we were just content with being able to make music for Africans that loved it, who wanted to dance and jubilate in our language and have fun with it because we had found something that we knew would definitely take over the world, but on that stage at the Barclays Center when we were outside of Africa and we were in New York City and it was packed. There were African artists on stage doing something that they loved, doing something that they believed in for so long, I think that was the moment when I knew it was going to turn into something else, and I think we’re there now.

We are headed towards a lot of collaboration between us and most of the international artists. I think right now we don’t have any boundaries because everybody is listening to Afrobeats. I believe no matter where you go, no matter the language barrier, the music has paved a way so large that nothing can break what is coming. It’s definitely something that will be possible. I believe that soon, we’re going to be making Afrobeats with Brazilian stars, and Spanish international stars, Chinese international stars. We’re carrying something. We have a message that we’re sending forth. I think the music is the fire behind everything because once you hear it, it’s unstoppable—and it’s been very magical to watch.

Tuma Basa, Director of Urban Music at YouTube

It might have been 2010. I had left NYC and had come back to visit—I missed my plane so I hung out a few hours in Brooklyn at a friend’s place. As I was taking a yellow taxi to JFK to catch my new plane, I heard Flava’s “Nwa Baby Remix” playing on the cab driver’s radio. It was Hot 97 during Jabba and Bobby Konders’ Sunday night show. I got so excited in that cab, I couldn’t believe it. I even had to verify that it wasn’t a CD! The “Sawa Sawa Sawalé” hook was an anthem at all the African parties in the States but it felt different hearing it on an actual FM Station. Mind you—we had already played 2Face’s “African Queen” on MTV Jams and a few other videos like “Ifana Ibaga” on an MTV2 special that Akon had hosted called “Worldwide Ting,” but I was involved with that, so this felt different. It was a different kind of organic. At the time, I didn’t imagine the current explosion, but it was the first sign of “crossing over” the seas that got me hyped like that. I’ll never forget it.

Phyno, Artist

The first time I felt like things were going to change before 2020 was when the Black Panther movie come out. I felt that vibe, like something was about to change—as if it was almost happening. Then, moments like Davido’s “Fall” getting bigger and Afro B’s ‘Joanna (Drogba), also Wizkid being on Drake’s album [Views]. Then lastly, the Beyoncé [The Lion King: The Gift] album. It was like “ok it’s time.”

We still have people back home doing their own thing, who will still change the game for good, like Zlatan, Naira Marley and Lil Kesh—I mean, real boys in the streets that are making their own sound. Making sure that things change. A whole lot is coming, trust me. What everybody is hearing now is just the tip of the iceberg. I think people here [in the US] probably know Burna Boy, Wizkid, Davido or Olamide. Trust me though, the wave is coming, afrobeats, Nigeria, Africa, this is culture to us. Music is what we do—everybody does music like it’s nothing.

Ivie Ani, Journalist, Culture Critic & Music Expert

When One Africa Music Fest came to New York for Barclays Center the summer of 2016, I remember thinking, “This is big.” It was the biggest afrobeats concert to come to New York. There was nothing of that magnitude happening in the city for African artists and it felt like it was only getting bigger. I missed the show, and remember regretting it. Wizkid, Burna Boy, Davido, Tiwa Savage,

By that time, Wizkid and Drake’s “One Dance” collaboration had been out for a few months already, but once he brought out Swizz Beatz during his set, it felt like the U.S. crossover was solidified.

A rapper from Queens named Chris Wattz introduced me to DJ Tunez in October 2017. Tunez had been doing his events in NY and I remember seeing his name on the bill for a bunch of African Student Union events at NYU from 2013 and on while I was an undergrad. His hit with Wande Coal, “Iskaba,” had been out for a year. At the time, I was writing for The Village Voice and I pitched my editor a profile on Tunez November 2017, and they agreed. At that time, I saw him as a conduit for Afrobeats in NY specifically. I chose to conduct the interview at a shop in St. Marks called Waga African Ethnic owned by a Burkinabé man I know named Ouenisongda Sawadogo. The interview never came out, but it was a big deal to have gotten the okay to run it at a place like the Voice.

Now that the crossover has happened, my concern is over how much of Afrobeats history wasn’t documented as meticulously as it deserves to have been. It feels like what I presume hip-hop felt like when its earnings and appeal started matching its popularity and acclaim and superseding the doubt of its lasting power. Afrobeats is a decade old and still feels nascent in a way. It’s still young, it still needs protection, it still needs direction. Afrobeats isn’t an overnight phenomenon, but something about it still feels refreshing and new. If we get this right— the documentation, the preservation, the ownership, the innovation—maybe this feeling can last just as long.

Sarkodie, Artist

*this quote was previously published in an interview from last month.

I knew that it was going to get to this point because we’ve always had it, it’s been with us for a very long time. We’ve had the swag, we’ve had the music, we’ve had everything. If you want the roots of blackness and the swag and everything that is portrayed in the States, the origin is Africa. We’ve always had the sound—it was just a matter of time. I knew that it was going to happen as soon as we unite and music showed us that unity is a very strong thing. I can testify that the whole “afrobeats invasion” happened when we started doing shows together. We started doing a lot of collaborations together and pushing our music out there. We started being more interested in ourselves—being in a club and not wanting to hear just R&B or hip hop but to hear afrobeats and be patriotic about where we’re from.

Abiodun ‘Bizzle’ Osikoya, Music A&R and Founder of “The Plug”

The year was 2015, a year which would set itself in lore of the rise of afrobeats. Nearing the middle of the year, rumors began that American superstar Drake was going to do a remix to Wizkid’s popular song “Ojuelegba,” a song which had a resounding impact in Nigeria at the time. The rumors turned out to be true, as indeed, Drake featured on a remix that also had Skepta on it, that brought the attention of the world to the Afrobeats sound—an attention that would be later reinforced when Drake then featured Wizkid on arguably the hottest song on his Views album: “One Dance”—a mixture of the best of both worlds.

A feeling of surprise and pride was in the air [when that song came out] and I felt it—for never had such a collaboration between the two worlds yielded such positive feedback, neither had it ever blended and worked so well. It was evident that a true paradigm shift was upon us. Africa was coming for the world.

Falz, Artist

I mean, personally I’ve always known that with the sheer amount of talent, and with how incredible the music we make on that side of the world is, I always knew that Afrobeats would eventually become a global sensation, it was just a matter of time. I’ve always truly believed that this would happen, I was just praying and hoping that it would happen in my time, and I’m just very excited to be a part of the movement.

Afro B, Artist

I’ll give you the Afro B timeline: I started promoting the genre in 2009 and 2010 in London. I was an Afrobeats DJ and at that time it didn’t have the popularity that it has today, but there was always a crowd that was ready to listen to the genre, and those were the “cool Africans” that grew up listening to the sound. I used to have a residency at a club called NW10 in Northwest London—week in, week out that’s where I would have a set and play the genre.

It started off as “what is this guy playing” from the people who weren’t African to those same people requesting songs or asking “what song was that.” But at the time it was mainly the [Francophone] music that was popping: Magic System, Koffi Olómide etc. That’s also when Mo’ Hits started with D’banj. I always knew it would get to where it is today because it’s a cultural thing, it’s a movement, not just a genre. It’s a lifestyle, so it can only get bigger from now, because more people are singing in English and the instrumentals are simpler than how they were before.

Before, the sound was quite complex, so to the average listener would think “what’s this.” There was a lot going on and people were singing [mostly] in their native languages, but now you hear more English or straight French or whatever it is. Now there’s a blend and crossover genres are happening, so you might hear a rapper over Afrobeats [production] or a Caribbean song that sounds kind of like Afrobeats or vice versa. That all plays a part in the sound elevating and it being easier for a consumer who is non-African to digest. All that needs to happen [for Afrobeats to go further] is more platforms co-signing the genre and putting it at the forefront. Artists like myself and others in the industry need to keep producing to encourage non-Africans to get with the wave. We’re at a time when people want to connect back to their roots in Africa. Entertainment is the fishing rod towards making that happen.

Bankulli, Singer, Songwriter, Talent Manager & Industry Expert

For me, a recognizable point was when D’banj’s “Oliver Twist” song picked up massively in the UK. We (Mo’ Hits Records), basically moved operations to the UK to properly understand what was going on and also to follow up with things. It all started with the song been played at the London Eye countdown into the new year. It’s an annual event where songs from different cultures in the UK are arranged in a playlist and played at the event going into the new year. It takes place at Hyde Park and over 250,000 people stay there to watch. They counted down to 2012 and the song was the first one played after the countdown. Also it was the [bicentennial] celebration of the Oliver Twist book, so it all coincide with the playing of the song at the London Eye. The song was a hit in Africa already and it picked up like fire on Twitter. The massive number of tweets about it instantly triggered support for it to be played on all mainstream radio station in the UK, including BBC Radio. It helped shape the present state of Afrobeats music because the genre got a lot of high-level push and promotion—and, of course, Kanye West made an appearance in the video which further cemented everything.

From all we have seen and heard, Afrobeats music is the fastest growing music genre in the world and it is not going to stop soon, especially with the increased availability of more social media platforms to that [allow] access for other cultures, and for more people to interact with the music. People dancing to it, and streaming the music makes it more [visible]. The sound is genuine, with spiritual vibes that can [translate] to listeners in many forms. The future is great for Afrobeats.

(Source: Okay Africa)