Barely days into the New Year, Burna Boy presented Nigeria its first taste of celebrity brouhaha. Initially happy with him being on the set list for the Coachella 2019, Burna Boy wasn’t the most impressed with his font size.

In a now-deleted Instagram Story, the Afro-fusion Nigerian artist hit out at Coachella organizers, writing: “@coachella I really appreciate you. But I don’t appreciate the way my name is written so small in your bill,” he wrote on Instagram. “I am an AFRICAN GIANT and will not be reduced to whatever that tiny writing means. Fix things quick please.”

Many people took to trolling him, saying he didn’t understand the rationale behind the Coachella font sizes. Some said his new found level of celebrity was getting to his head; a select few supported the ‘Ye’ singer, rubbishing the veiled ‘politics’ surrounding the fonts.

The words – ‘Burna Boy’, ‘Coachella’, ‘African Giant’ – trended, when the time came, Burna Boy performed on the Coachella stage, in an outfit as crazy as his performance. He wasn’t done with the controversy, however, as he’s been engaged in public spats with social media users, the unsavoury words of “backwards unprogressive fools” coming up sometime.

Markers were being raised. If Burna Boy wasn’t careful, he would fall out of the people’s love, it seemed. Since 2012, he’d been on his grind, steadily building his brand. Veer into the mind of the observer and the worry would arise: could Burna Boy, born through his antics, be responsible for his own downfall? A reviewer of Burna Boy’s Outside album, Dennis Peter, had written of the artiste, that “Embedded within Burna Boy is a flagrant character matrix with an unending penchant for causing controversy, and a constant fixation for an exciting press that’s always eager to cast the artist in his controversial light. The ever prominent dramas probably wouldn’t cause much noise or be of much consequence if Burna wasn’t a generational talent.”

Are these, however, in lieu of his current position in African music, enough to bring down Burna Boy? We look towards his history of controversy, of which its zenith was the reported involvement of the act in a stabbing which took place in London. According to a well-flouted story, Burna Boy was tried as a minor and sentenced to jail. Eleven months later, when he was released on parole, he came back to Nigeria. In a song, ‘Freedom’, he seems to hint at a troubled past as he sings, “tell me what I gotta do to prove to you that I’m a changed man?” Then there’s the Mr. 2kay incident, where Burna Boy allegedly sent robbers to his industry colleague’s house. He’s also had his peace about meting out violence to bloggers and pastors.

In relativity to his more recent misgivings, one finds more ‘lenient’ acts from the dreadlocked singer. His fans recognize that he can’t fully “give in” to being an entirely likeable character. And there’s a compromise. He’s a musical genius, after all, they seem to say with a shrug when another ‘forgivable’ Burna Boy news comes their way. This also plays into a grander narrative of Burna Boy being a kind of embodiment for youthful revolution. His constant recycling of Fela chants and melodies, his public use of marijuana, his voice and personality, the intellectual quality inherent in his music – he is today’s youth. And the drama is a part of what makes him so appealing.

However, since he has always been controversial, it would pose a serious question as to why he hadn’t been as big as he is now then. It would appear to be that the answer to that question is “Burna Boy finally understands”. From early 2018 to the present moment, his moves on and off the studio has been latent with purposefulness.

‘Ye’, unarguably the anthem of last year, was everyone’s jam. From London to Nairobi to the Coachella stage, people loved ‘Ye’ and more often than not, would sing its lyrics word for word. That was, however, an exception: Burna Boy would become expert in utilising his versatility so that each demography that made up strong portions of his fan base got unique content.

It played into our very eyes with ‘Gbona’ and ‘On The Low’. Both songs were afropop, catchy vibes and all, instantly recognizable as African. The man knew that he had to consolidate on his hometown success after he’d given the largest cut of his album Outside to the UK. He would later do the most with ‘Killin Dem’, a collaboration with Zlatan Ibile, the hottest rapper in Nigeria, the one behind the Zanku dance rave. Expectedly, the song was a massive success, topping video and download/streaming charts for quite some time. One would think that Burna Boy would rest a bit, enjoy the view of his shiny castle from an elevated place. He most recently released ‘Dangote’, a song which, once more, glorifies the hustle inherent in today’s youth. Name dropping Nigeria’s richest man, he asks rhetorically: “Dangote still dey find money…why me no find money?”

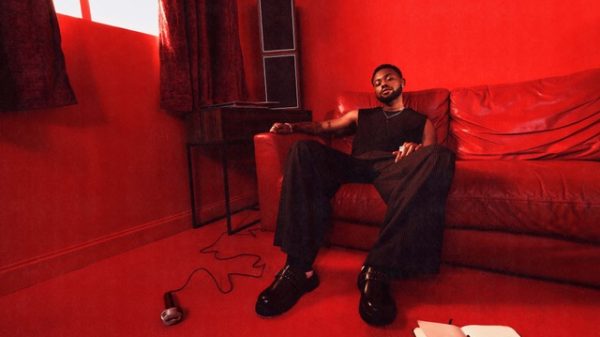

He also served his outside (pun intended) market once more, releasing Steel and Copper, a four-track collaboration with Los Angeles producer duo DJDS. The sound is switched, Burna Boy touches on themes of survival as if he was cast back into the world, naked in his sins. On ‘Thuggin’, he sings “I’m still thugging anyway.” The video, which has been described as ‘impressionistic’ is further proof of Burna Boy’s understanding of his target market. Whereas the majority of the African gaze favours the outlandish in visuals, the outside community wants to sit before their TV screens, keenly eyed, asking: “why did he do that?”

This, more than anything else, has proven to be a serious tool Burna Boy has employed in dealing with the demands from fans with different cultural leanings. By giving parts of him strategically, he has managed to keep control of the what resides at the centre of his being: brute confidence that surely, he can do it all.

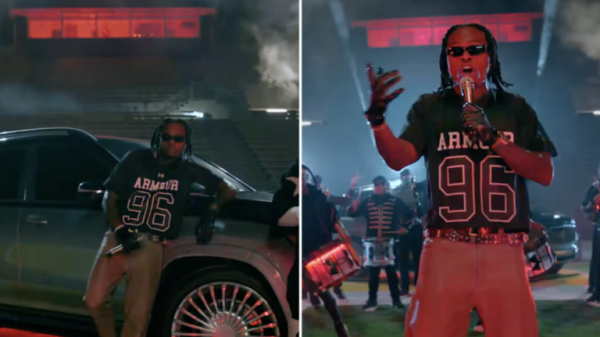

Watch current Burna Boy’s music video, On The Low.

(Source: Pan African Music)